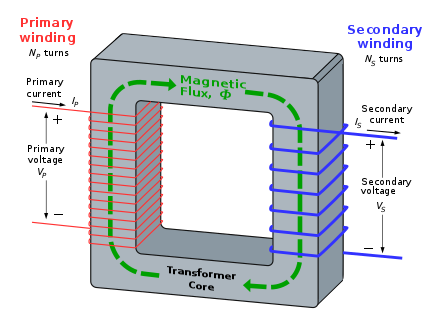

A transformer is a static electrical device that transfers electrical energy between two or more circuits. A varying current in one coil of the transformer produces a varying magnetic flux, which, in turn, induces a varying electromotive force across a second coil wound around the same core. Electrical energy can be transferred between the two coils, without a metallic connection between the two circuits. Faraday's law of inductiondiscovered in 1831 described the induced voltage effect in any coil due to changing magnetic flux encircled by the coil.

Transformers are used for increasing or decreasing the alternating voltages in electric power applications, and for coupling the stages of signal processing circuits.

Since the invention of the first constant-potential transformer in 1885, transformers have become essential for the transmission, distribution, and utilization of alternating current electric power.[2] A wide range of transformer designs is encountered in electronic and electric power applications. Transformers range in size from RFtransformers less than a cubic centimeter in volume, to units weighing hundreds of tons used to interconnect the power grid.

Principles

Ideal transformer equations

By Faraday's law of induction:

Where  is the instantaneous voltage,

is the instantaneous voltage,  is the number of turns in a winding, dΦ/dt is the derivative of the magnetic flux Φ through one turn of the winding over time (t), and subscripts P and S denotes primary and secondary.

is the number of turns in a winding, dΦ/dt is the derivative of the magnetic flux Φ through one turn of the winding over time (t), and subscripts P and S denotes primary and secondary.

Combining the ratio of eq. 1 & eq. 2:

Turns ratio  . . . (eq. 3)

. . . (eq. 3)

Where for a step-down transformer a > 1, for a step-up transformer a < 1, and for an isolation transformer a = 1.

By law of conservation of energy, apparent, real and reactive power are each conserved in the input and output:

Where  is winding self-inductance.

is winding self-inductance.

By Ohm's law and ideal transformer identity:

Where  is the load impedance of the secondary circuit &

is the load impedance of the secondary circuit &  is the apparent load or driving point impedance of the primary circuit, the superscript

is the apparent load or driving point impedance of the primary circuit, the superscript  denoting referred to the primary.

denoting referred to the primary.

Ideal transformer

An ideal transformer is a theoretical lineartransformer that is lossless and perfectly coupled. Perfect coupling implies infinitely high core magnetic permeability and winding inductances and zero net magnetomotive force (i.e. ipnp - isns = 0).[5][c]

Ideal transformer connected with source VP on primary and load impedance ZL on secondary, where 0 < ZL < ∞.

A varying current in the transformer's primary winding attempts to create a varying magnetic flux in the transformer core, which is also encircled by the secondary winding. This varying flux at the secondary winding induces a varying electromotive force (EMF, voltage) in the secondary winding due to electromagnetic induction and the secondary current so produced creates a flux equal and opposite to that produced by the primary winding, in accordance with Lenz's law.

The windings are wound around a core of infinitely high magnetic permeability so that all of the magnetic flux passes through both the primary and secondary windings. With a voltage source connected to the primary winding and a load connected to the secondary winding, the transformer currents flow in the indicated directions and the core magnetomotive force cancels to zero.

According to Faraday's law, since the same magnetic flux passes through both the primary and secondary windings in an ideal transformer, a voltage is induced in each winding proportional to its number of windings. The transformer winding voltage ratio is directly proportional to the winding turns ratio. [7]

The ideal transformer identity shown in eq. 5 is a reasonable approximation for the typical commercial transformer, with voltage ratio and winding turns ratio both being inversely proportional to the corresponding current ratio.

The load impedance referred to the primary circuit is equal to the turns ratio squared times the secondary circuit load impedance.[8]

Real transformer

Deviations from ideal transformer

The ideal transformer model neglects the following basic linear aspects of real transformers:

(a) Core losses, collectively called magnetizing current losses, consisting of[9]

- Hysteresis losses due to nonlinear magnetic effects in the transformer core, and

- Eddy current losses due to joule heating in the core that are proportional to the square of the transformer's applied voltage.

(b) Unlike the ideal model, the windings in a real transformer have non-zero resistances and inductances associated with:

- Joule losses due to resistance in the primary and secondary windings[9]

- Leakage flux that escapes from the core and passes through one winding only resulting in primary and secondary reactive impedance.

(c) similar to an inductor, parasitic capacitance and self-resonance phenomenon due to the electric field distribution. Three kinds of parasitic capacitance are usually considered and the closed-loop equations are provided [10]

- Capacitance between adjacent turns in any one layer;

- Capacitance between adjacent layers;

- Capacitance between the core and the layer(s) adjacent to the core;

Inclusion of capacitance into the transformer model is complicated, and is rarely attempted; the ‘real’ transformer model’s equivalent circuit does not include parasitic capacitance. However, the capacitance effect can be measured by comparing open-circuit inductance, i.e. the inductance of a primary winding when the secondary circuit is open, to a short-circuit inductance when the secondary winding is shorted.

Equivalent circuit

Referring to the diagram, a practical transformer's physical behavior may be represented by an equivalent circuit model, which can incorporate an ideal transformer.[16]

Winding joule losses and leakage reactances are represented by the following series loop impedances of the model:

- Primary winding: RP, XP

- Secondary winding: RS, XS.

In normal course of circuit equivalence transformation, RS and XS are in practice usually referred to the primary side by multiplying these impedances by the turns ratio squared, (NP/NS) 2 = a2.

Core loss and reactance is represented by the following shunt leg impedances of the model:

- Core or iron losses: RC

- Magnetizing reactance: XM.

RC and XM are collectively termed the magnetizing branch of the model.

Core losses are caused mostly by hysteresis and eddy current effects in the core and are proportional to the square of the core flux for operation at a given frequency.[9] :142–143 The finite permeability core requires a magnetizing current IM to maintain mutual flux in the core. Magnetizing current is in phase with the flux, the relationship between the two being non-linear due to saturation effects. However, all impedances of the equivalent circuit shown are by definition linear and such non-linearity effects are not typically reflected in transformer equivalent circuits.[9]:142 With sinusoidal supply, core flux lags the induced EMF by 90°. With open-circuited secondary winding, magnetizing branch current I0 equals transformer no-load current.[16]

The resulting model, though sometimes termed 'exact' equivalent circuit based on linearity assumptions, retains a number of approximations.[16] Analysis may be simplified by assuming that magnetizing branch impedance is relatively high and relocating the branch to the left of the primary impedances. This introduces error but allows combination of primary and referred secondary resistances and reactances by simple summation as two series impedances.

Transformer equivalent circuit impedance and transformer ratio parameters can be derived from the following tests: open-circuit test, short-circuit test, winding resistance test, and transformer ratio test.

No comments:

Post a Comment